Another day, another prominent rock star canceling a show to protest a controversial new law in a Southern state.

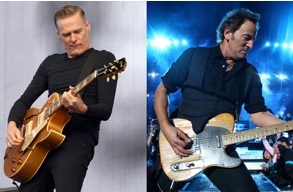

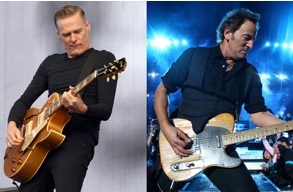

Bryan Adams announced Sunday night that he was canceling a scheduled concert in Mississippi to protest a law that will let businesses as well as state employees refuse services to gay people. Adams’s announcement comes on the heels of Bruce Springsteen’s decision to cancel a concert in North Carolina to take a stand against a new law there that bars local governments from extending civil rights protections to gay and transgender people.

I have met both these artists before and have seen their shows, there is no question about their talent and both are very likeable chaps.

The question really isn’t what musicians say or don’t say about social issues or politics. The real issue is the weight that people give to the opinions expressed by popular musicians.

Musicians should of course enjoy as much right to expressing their opinion as anyone else does in the polity in which they’re living and working—but the people to whom they’re expressing their opinions should evaluate those ideas rationally and on their own merits, without giving them greater weight just because they came from someone who is a popular artist today, keeping in mind that popularity has a tendency to change with the wind.

Music became the voice, in many ways, of the counterculture of the sixties. Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Buffalo Springfield and many other artists and musicians engaged with the political issues of the day (chiefly the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War) and wrote songs that became important protest anthems.

But the expectation that this should be the norm—that thereafter artists would or should carry on in that tradition, forming the vanguard of a counterculture, their music and lyrics ever after suffused with trenchant and powerful political ideas to whom all should look is a little far-fetched. It was, to be sure, something that happened again in other contexts and other times: Underground rock bands. played a role, for example, in the Czech opposition movement, and in China’s 1989 student movement, where the song “Nothing to my Name” by China’s greatest rock musician, Cui Jian, captured the spirit of a movement.

The fact is, musicians aren’t really so different from anyone else in terms of their insights into, their knowledge of, and their savvy about politics and social issues. But why should anyone put more stock in their political and social opinions than of a carpenter or brick layer ?

Kaiser Kuo, the founding member of Tang Dynaty had this to say: “As someone who was, for a number of years, a member of a rock band that was quite famous in China in the aftermath of 1989. My band, which was called Tang Dynasty, sold millions of records and topped charts both in the mainland and in Taiwan. But the guys in the band had incredibly shallow historical knowledge, no real interest in politics, and no special insight into and no particular passion for affairs of state. I was notionally “interested” and sure, I had passions, but at least I understood that these were no match for the sheer enormousness of my ignorance”.

“I figured out very early on that most of the issues that people expected us to take some kind of a stand on were actually really, really complex. And so I generally told people who tried to parse our lyrics for political messages, or who wanted our opinion on the great issues of the day, that there was nothing to see here, that they should move along. I would tell them, “Look, if you want to engage in politics, write books. Write articles. Write pamphlets. Make speeches. Don’t reduce complex political ideas to the rhyming verses and repeating choruses of a three-minute pop song. Doing so, you’re only creating slogans—and God knows if there’s one thing Chinese politics need less of, it’s slogans.”

Musicians, again, have as much or as little right to political expression as anyone else. And once in a generation or so you’ll have a Dylan, or a Cui Jian. But I would urge all musicians to remember that the more famous among them also enjoy something of a bully pulpit, and that they can, in the combination of music and words, stir passions in their audiences. That can easily devolve into demagoguery. They should be mindful of that possibility. But more importantly, their audiences should be mindful of that possibility, and evaluate the political content of the music they’re consuming with healthy skepticism.