“A man who is not courageous enough to take risks will never accomplish anything in life.” – Muhammad Ali

Normally, I stick to music related subjects, but if we are to expand that a little broader to the world of entertainment, I would have to include Muhammad Ali. He was not only a legend in the sports world, but he has definitely left his mark on the entertainment world as well.

(excerpts taken from Tim Dahlberg of the AP June 4, 2016)

He was fast of fist and foot — lip, too — a heavyweight champion who promised to shock the world and did. He floated. He stung. Mostly he thrilled, even after the punches had taken their toll and his voice barely rose above a whisper.

He was The Greatest.

Muhammad Ali died yesterday (Friday) at age 74. He was hospitalized in the Phoenix area with respiratory problems earlier this week, and his children had flown in from around the country.

“It’s a sad day for life, man. I loved Muhammad Ali, he was my friend. Ali will never die,” Don King, who promoted some of Ali’s biggest fights, told The Associated Press early Saturday. “Like Martin Luther King his spirit will live on, he stood for the world.”

A funeral will be held in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. The city held a memorial service today (Saturday).

With a wit as sharp as the punches he used to “whup” opponents, Ali dominated sports for two decades before time and Parkinson’s disease, triggered by thousands of blows to the head, ravaged his magnificent body, muted his majestic voice and ended his storied career in 1981.

He won and defended the heavyweight championship in epic fights in exotic locations, spoke loudly on behalf of blacks, and famously refused to be drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War because of his Muslim beliefs.

Despite his debilitating illness, he traveled the world to rapturous receptions even after his once-bellowing voice was quieted and he was left to communicate with a wink or a weak smile.

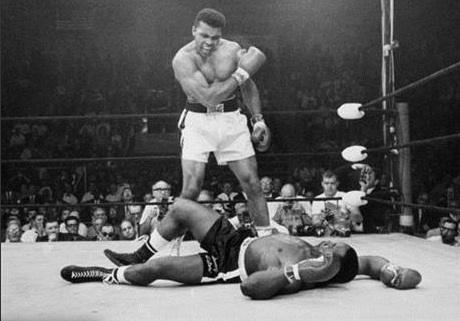

Revered by millions worldwide and reviled by millions more, Ali cut quite a figure, 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds in his prime. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” his cornermen exhorted, and he did just that in a way no heavyweight had ever fought before.

He fought in three different decades, finished with a record of 56-5 with 37 knockouts — 26 of those bouts promoted by Arum — and was the first man to win heavyweight titles three times.

He beat the fearsome Sonny Liston twice, toppled the mighty George Foreman with the rope-a-dope in Zaire, and nearly fought to the death with Joe Frazier in the Philippines.

His fights were so memorable that they had names — “Rumble in the Jungle” and “Thrilla in Manila.”

But it was as much his antics — and his mouth — outside the ring that transformed the man born Cassius Clay into a household name as Muhammad Ali.

“I am the greatest,” Ali thundered again and again. Few would disagree.

He defied the draft at the height of the Vietnam war — “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” — and lost 3 1/2 years from the prime of his career. He entertained world leaders, once telling Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos: “I saw your wife. You’re not as dumb as you look.”

Parkinson’s robbed him of his speech. It took such a toll on his body that the sight of him in his later years — trembling, his face frozen, the man who invented the Ali Shuffle now barely able to walk — shocked and saddened those who remembered him in his prime.

The quiet of Ali’s later life was in contrast to the roar of a career that had breathtaking highs along with terrible lows. He exploded on the public scene with a series of nationally televised fights that gave the public an exciting new champion, and he entertained millions as he sparred verbally with the likes of bombastic sportscaster Howard Cosell.

Ali once calculated he had taken 29,000 punches to the head and made $57 million in his pro career, but the effect of the punches lingered long after most of the money was gone. That didn’t stop him from traveling tirelessly to meet with world leaders and champion legislation dubbed the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. While slowed in recent years, he still managed to make numerous appearances, including a trip to the 2012 London Olympics.

Despised by some for his outspoken beliefs and refusal to serve in the U.S. Army in the 1960s, an aging Ali became a poignant figure whose mere presence at a sporting event would draw long standing ovations.

He lit the Olympic torch for the 1996 Atlanta Games in a performance as riveting as some of his fights.

A few years after that, he sat mute in a committee room in Washington, his mere presence enough to persuade lawmakers to pass the boxing reform bill that bore his name.

Members of his inner circle weren’t surprised. They had long known Ali as a humanitarian who once wouldn’t think twice about getting in his car and driving hours to visit a terminally ill child. They saw him as a man who seemed to like everyone he met — even his archrival Frazier.

“I consider myself one of the luckiest guys in the world just to call him my friend,” former business manager Gene Kilroy

One of his biggest opponents would later become a big fan, too. On the eve of the 35th anniversary of their “Rumble in the Jungle,” Foreman paid tribute to the man who so famously stopped him in the eighth round of their 1974 heavyweight title fight, the first ever held in Africa.

“I don’t call him the best boxer of all time, but he’s the greatest human being I ever met,” Foreman said. “To this day he’s the most exciting person I ever met in my life.”

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay on Jan. 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky, Ali began boxing at age 12 after his new bicycle was stolen and he vowed to policeman Joe Martin that he would “whup” the person who took it.

He was only 89 pounds at the time, but Martin began training him at his boxing gym, the beginning of a six-year amateur career that ended with the light heavyweight Olympic gold medal in 1960.

After he beat Liston to win the heavyweight title in 1964, Ali shocked the boxing world by announcing he was a member of the Black Muslims — the Nation of Islam — and was rejecting his “slave name.”

As a Baptist youth he spent much of his time outside the ring reading the Bible. From now on, he would be known as Muhammad Ali.

Ali’s affiliation with the Nation of Islam outraged and disturbed many white Americans, but it was his refusal to be inducted into the Army that angered them most.

That happened on April 28, 1967, a month after he knocked out Zora Folley in the seventh round at Madison Square Garden in New York for his eighth title defense.

He was convicted of draft evasion, stripped of his title and banned from boxing.

Ali appealed the conviction on grounds he was a Muslim minister. During his banishment, Ali spoke at colleges and briefly appeared in a Broadway musical called “Big Time Buck White.” Still facing a prison term, he was allowed to resume boxing three years later, and he came back to stop Jerry Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, in Atlanta despite efforts by Georgia Gov. Lester Maddox to block the bout.

He was still facing a possible prison sentence when he fought Frazier for the first time on March 8, 1971, in what was labeled “The Fight of the Century.”

A few months later the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction on an 8-0 vote.

Perhaps his most memorable fight was the “Rumble in the Jungle,” when he upset a brooding Foreman to become heavyweight champion once again at age 32.

Many worried that Ali could be seriously hurt by the powerful Foreman, who had knocked Frazier down six times in a second round TKO.

But while his peak fighting days may have been over, he was still in fine form verbally. He promoted the fight relentlessly, as only he could.

Ali pulled out a huge upset to win the heavyweight title for a second time, allowing Foreman to punch himself out. He used what he would later call the “rope-a-dope” strategy — something even trainer Angelo Dundee knew nothing about.

Finally, he knocked out an exhausted Foreman in the eighth round, touching off wild celebrations among his African fans.

He spouted poetry and brash predictions. After the sullen and frightening Liston, he was a fresh and entertaining face in a sport that struggled for respectability.

At the weigh-in before his Feb. 25, 1964, fight with Liston, Ali carried on so much that some observers thought he was scared stiff and suggested the fight in Miami Beach be called off.

“The crowd did not dream when they lay down their money that they would see a total eclipse of the Sonny,” Ali said.

Ali went on to punch Liston’s face lumpy and became champion for the first time when Liston quit on his stool after the sixth round.

“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” became Ali’s rallying cry.

His talent for talking earned him the nickname “The Louisville Lip,” but he had a new name of his own in mind: Muhammad Ali.

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he told reporters the morning after beating Liston. “I’m free to be who I want.”

By the time Ali was able to return to the ring following his forced layoff, he was bigger than ever. Soon he was in the ring for his first of three epic fights against Frazier, with each fighter guaranteed $2.5 million.

Before the fight, Ali called Frazier an “Uncle Tom” and said he was “too ugly to be the champ.” His gamesmanship could have a cruel edge, especially when it was directed toward Frazier.

In the first fight, though, Frazier had the upper hand. He relentlessly wore Ali down, flooring him with a crushing left hook in the 15th round and winning a decision.

It was the first defeat for Ali, but the boxing world had not seen the last of him and Frazier in the ring. Ali won a second fight, and then came the “Thrilla in Manila” on Oct. 1, 1975, in the Philippines, a brutal bout that Ali said afterward was “the closest thing to dying” he had experienced.

Ali won that third fight but took a terrific beating from the relentless Frazier before trainer Eddie Futch kept Frazier from answering the bell for the 15th round.

“They told me Joe Frazier was through,” Ali told Frazier at one point during the fight.

“They lied,” Frazier said, before hitting Ali with a left hook.

The fight — which most in boxing agree was Ali’s last great performance — was part of a 16-month period on the mid-1970s when Ali took his show on the road, fighting Foreman in Zaire, Frazier in the Philippines, Joe Bugner in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and Jean Pierre Coopman in Puerto Rico.

The world got a taste of Ali in splendid form with both his fists and his mouth.

Ali would go on to lose the title to Leon Spinks, then come back to win it a third time on Sept. 15, 1978, when he scored a decision over Spinks in a rematch before 70,000 people at the Superdome in New Orleans.

In 1990, he went to Iraq on his own initiative to meet with Saddam Hussein and returned to the United States with 15 Americans who had been held hostage.

Ali didn’t complain about the price he had paid in the ring. “What I suffered physically was worth what I’ve accomplished in life,” he said in 1984.