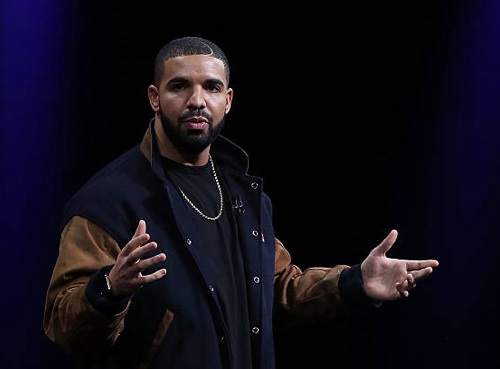

A few weeks ago, a New York federal judge ruled that Hip-Hop Artist Drake was protected by copyright’s fair use doctrine when he sampled a spoken-word jazz track on his 2013 song “Pound Cake,” saying the artist had transformed the purpose of the clip. Drake used 35 seconds of Jimmy Smith’s 1982 “Jimmy Smith Rap” without clearing the clip, but Judge William H. Pauley said Drake’s purpose in doing so was sharply different from the original artist’s goals in creating it.

Drake’s recent copyright victory is noteworthy because rulings of fair use are rare in songwriting. When it comes to documentaries and less abstract art forms, judges can figure out whether use of copyrighted material is transformative, however, in disputes over song sampling, parties have tended to wage fights over other issues like ownership records and whether the copying is sufficiently substantial.

Morgan Pietz, partner at Gerard Fox Law recently sat down with IPWatchdog to discuss Drake’s case and what it means to music copyright. In his role, Pietz primarily handles intellectual property and entertainment matters, business disputes, class actions, and related insurance issues.

“What is extremely unusual about this case is that the defendants got out of it relatively early on, at the summary judgment stage,” he explained. “The nature of the fair use defense is such that it turns on facts, so a defendant normally must take a fair use case all the way to trial, and take their chances with a jury, to get a determination that what they did is a fair use such that they should be absolved of liability.”

So, it is usually very risky to rely on fair use as a defense because you are normally going to have to spend hundreds of thousands or millions in legal fees to defend a case all the way through to trial. Also, you are at the mercy of the jury, and if you lose, you might end up paying millions in damages as well as perhaps the other side’s legal fees. Pietz added, “Whenever clients come to me insisting that whatever it is they are doing is fair use, I usually tell them that you may well be right, but do you feel strongly enough about that to pay six or seven figures to find out?”

In the judge’s perspective, this small change totally changed the meaning such that the statement was being used for an entirely different purpose than the original, such that it was transformative and thus fair use, according to Pietz. “Nobody really knows what changes the nature or purpose of a work or makes a use transformative. We now have this judge’s take on how these questions should be answered in this particular case,” he explained. “But a different judge, or a jury, for that matter, could have tried to answer them by focusing on totally different aspects of this situation.”

“In my view, the four fair use factors, as well as the idea of a transformative use, are all concepts that are so incredibly vague and open to interpretation that grounding a defense on these concepts is always a risky bet.”

So, how exactly can artists who use song clips protect themselves from copyright infringement in the future?

If an artist is sampling music or spoken word from an older sound recording, then the artist needs to clear both the sound recording and the composition, according to Pietz. In this case, Drake’s people cleared and licensed the sound recording, however, they didn’t clear the composition – and they got sued.

“This case is the exception that proves the rule,” he said. “Defendants assert fair use all the time, in sampling cases especially. But it seems like it is very rare that a defendant sticks in the fight long enough to actually succeed in getting rid of a case based on a fair use defense as happened here.”

Back in April 2010 folksinger Joni Mitchell slandered Bob Dylan in the LA Times, accusing him of plagiarism. The debate over why Mitchell delivered the ultimate insult varied. “Envy” some proclaimed, while others chalked it up to interviewer Matt Diehl’s ill-advised attempt to compare Mitchell with Bob Dylan: “The folk scene you came out of had fun creating personas.

“You were born Roberta Joan Anderson, and someone named Bobby Zimmerman became Bob Dylan.” And an inflamed Mitchell fired back: “Bob is not authentic at all, “he’s a plagiarist.” “Plagiarist” is a mighty bold word to be flicking at anyone.

Back in June 2009, Christie’s of New York auctioned one of Dylan’s earliest handwritten poems. “Little Buddy,” scribbled in blue ink in crooked kid writing on a sheet of paper. Proudly signed “Bobby Zimmerman,” Dylan wrote the poem in 1957 and submitted it to The Herzl Herald, his Jewish summer camp paper. Less than 24 hours after Christie’s announced the auction, somebody phoned Reuter News Service saying that the poem was actually an old Hank Snow song titled, incidentally, “Little Buddy.” Snow released the song in the 1940s on a 78 RPM album, a copy of which the Zimmermans—big fans of the country singer—certainly had in their collection.

Innocent as it was, obviously nobody ever schooled young Bobby Zimmerman on copyright infringement. But this poem is a very early example of Dylan’s style of borrowing lyrics and melodies from various songs and stitching them together to form his own creations.

But is it Plagiarism?

While Bobby Zimmerman’s outright theft of Snow’s lyrics is indeed plagiarism, whether his later work falls under that category is a matter of debate. There’s a very fine line between what constitutes plagiarism and the thing called “pastiche” which the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines as, “a literary, artistic, musical, or architectural work that imitates the style of previous work,” or, “a musical, literary, or musical composition made up of selections of different works.”

A good portion of Dylan’s canon falls under both of those definitions and accounts for much of his genius. In American folk music, it’s been a long-standing tradition to cut and paste from the songs of preceding generations. It’s not only encouraged, but expected, and upon his 1961 arrival in New York, Dylan quickly proved his mastery at the form, borrowing not only from his musical idol, Woody Guthrie, but from old folk songs and American blues in the public domain.

For instance, 1962’s “The Ballad of Hollis Brown” owes it’s melody to the 1920s ballad, “Pretty Polly,” while the arrangement for “Masters of War” was taken from Jean Ritchie’s “Nottamun Town,” an English folk song whose roots date back to the middle ages.

Modern Times (2006) became Dylan’s most controversial record in regards to blatantly lifting lyrics and melodies—without crediting the original authors. While it was nothing new for Dylan, some fans were unfamiliar with the idea of pastiche and how largely it figured into Dylan’s songwriting style. After the album’s release, scholars noted that lyrics in several songs were strikingly similar to the work of Civil War-era Confederate poet, Henry Timrod.

While Dylan borrowed fragments of Timrod’s poetry for “When the Deal Goes Down,” the melody is based on Bing Crosby’s staple hit, “Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day).” On another note, Dylan used Muddy Waters’ blues arrangement practically note for note in “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” changing most of the lyrics but keeping the title. Dozens of these instances pepper the entire album. However, the album liner notes state, “All songs written by Bob Dylan.”

Many contemporary music critics and professors argue that pastiche is the most culturally advanced form of creative expression today, which would partly account for Dylan’s massive success as a songwriter. Likewise, hip hop and DJ electronica explore pastiche with the use of samples from other songs. As far as borrowing melodies, Beck’s song “Loser” sounds frighteningly close to the Allman Brother Band’s hit “Midnight Rider,” while Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” blatantly borrowed the bass line from Queen/David Bowie’s hit “Under Pressure.”

Whether Dylan’s controversial use of other artist’s lines and melodies is ethical is the decision of the listener. But Dylan has always seen songs in the public domain as templates to build upon, and his borrowing of others’ material is more likely his way of paying tribute to those who have had a major influence on him. In turn, next-generation artists often pay homage to Dylan for the impact he had on their music.