On almost every complex issue, intelligent people who have been exposed to the same information still reach different and even contradictory conclusions. It turns out that the human mind cannot deal with high levels of uncertainty. When we try to analyze many, often contradictory, pieces of evidence with differing levels of reliability, human conclusions often prove incredibly inaccurate.

Unfortunately, analyses carried out in the real world are rarely built on entirely accurate and unbiased foundations. Studies consistently find that people ignore or underestimate evidence that is inconsistent with their existing beliefs.

Furthermore, even before we add our own biases, the information available to us has already been heavily filtered and distorted. The media’s incentives are partly to blame for this. There are very few media organizations whose main incentive is the accurate reporting of facts. Most seek to maximize profit, while others are funded to promote specific agendas or ideologies. High quality investigative journalism is expensive and ultimately does not attract significantly more traffic or revenue than fluff entertainment or superficial PR pieces.

Going one step further, the information available to the media is also biased. Stories that are beneficial to commercial or political interests are presented in neatly organized PR pieces, while special efforts are undertaken to conceal damaging information. In security-related matters, governments typically control the release of information, favoring journalists that are deemed friendly and non-threatening over journalists who are more critical in their reporting. This creates a deterrence effect and harms journalistic integrity.

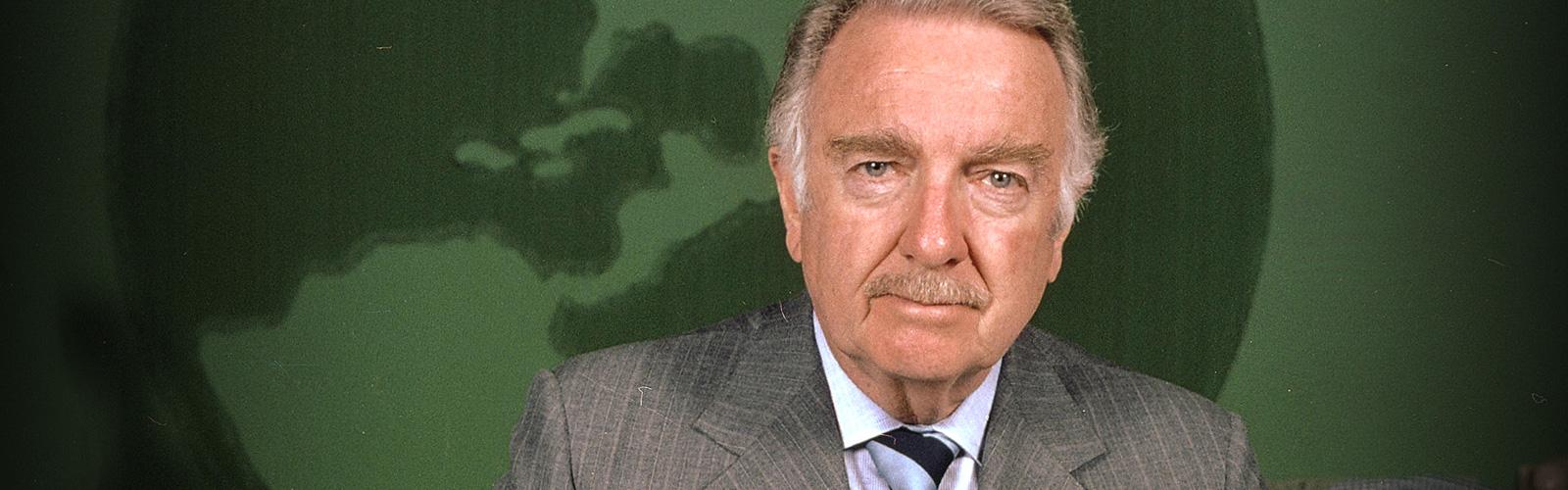

As a teenager, I grew up watching the evening news with Walter Cronkite as the anchorman for CBS News, and one of the big stories he covered was the war in Vietnam; for several years, the veteran newscaster was no different from most of his colleagues, reporting the story from the framework that had been laid out by Lyndon Johnson ‘s White House and the Pentagon, that the conflict was a winnable war, necessary to prevent a string of vital nations from flipping Communist like a set of dominoes. But as the U.S. death toll rose sharply in early 1968’s Tet Offensive, Cronkite’s instincts told him it was critical that he see for himself what was really happening halfway around the world, and that he report his findings honestly to the American people.

And what Cronkite found in early 1968 shocked him, as best recounted by another greatly missed journalist of that era, the late David Halberstam, in his book “The Powers that Be.” Early in his trip, Cronkite went to the South Vietnamese city of Hue, which U.S. generals assured the newsman had been “pacified,” only to find himself in the middle of a deadly firefight, finally airlifted out of the city with the body bags containing 12 young American GIs. Halberstam wrote that Cronkite was “moved by what he had seen, the immediacy and potency of it all, the destruction and the loss and the killing, and the fact that it was begetting so many lies, first by the command here in Saigon and then by the Administration in Washington.”

The impact of one lone journalist’s decision was monumental. At the end of his special report that aired on CBS, Cronkite told viewers that “we have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds.” Then he explained that it seemed certain that “the bloody experience in Vietnam is to end in a stalemate,” ending his editorial this way:

“To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, if unsatisfactory, conclusion. It is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy and did the best they could. This is Walter Cronkite, good night.”

President Johnson famously told aides that “if I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” A month later. LBJ stunned America with the news that he would not seek another term and peace talks began shortly after that. There was no Hollywood ending — U.S. combat dragged on for five long years, but the fulcrum had tipped with Cronkite, as the main focus turned to ending the war rather than expanding it. A few years later, Cronkite saw a similar gathering threat to the American body politic in the Watergate scandal, and CBS was alone in devoting two lengthy reports to that abuse of power, well ahead of the competition. Cronkite never lost his journalist’s instincts for thorough reporting, but he also understood something very important, much as his CBS predecessor Edward R. Murrow had shown with Joe McCarthy a generation earlier.

Cronkite understood that the ultimate role that journalism can be forced to play in democracy is, quite simply, to fight to preserve democracy itself, and that the greatest threat to our republic was when elected leaders choose to lie to the American people. That didn’t mean abandoning the core principles of journalism — aggressive fact finding, which includes first-hand observation and talking to all sides, as Cronkite did on his trip to Vietnam, or an innate sense of fairness and justice. But he knew that journalism was more than rote stenography —parroting the untruths that LBJ and the Pentagon said about the war and finding a political opponent to quote deep down in the story for “balance.” He knew there could be a time when the only way to inform the American people of a higher truth was to step outside the straight jacket of objectivity.

To turn a famous phrase on its head, Cronkite realized there are times when a true journalist does yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater…when there is an actual fire. It is not an easy call to make, but Cronkite did the right thing, displaying real courage. Because of what Cronkite did in 1968, some people who would have perished were able to get out alive.

Walter Cronkite lived on for a long time, long enough to see the consequences when there was no one with his bravery and his journalistic principles in a similar position of influence.

So much has been written about the man, about his rare tone of authority, , the incredible events that he reported from moon walks to the Kennedy assassination. All those things are true, but they also tend to miss how he was willing to risk all of that because he felt his responsibility to his country and to the truth was more important than his career. That he could make such a choice was the true meaning of Walter Cronkite.

Our world is very different from 1968, and it’s not clear if any one news person could have the amount of influence that Cronkite could have for one night. But, hopefully, on some canvass’s journalists are engaged in a quest for real truth and not an artificially manufactured one, the spirit of Walter Cronkite is still alive.