Several years ago at the South by Southwest festival, Lady Gaga invited a performance artist to vomit on her, in a move that likely provoked some to question her artistic vision, if not her sanity. For others the act probably only added to her mystique, rendering her music that much more enjoyable. New research demonstrates that an artist’s eccentricity, even in realms irrelevant to the medium of expression, can enhance our perception of the artist’s work. But there’s a catch: The oddball behavior can’t feel like a gimmick.

In many of the fans minds, eccentricity and creativity go together like, well, Bjork and swans. Just as generating a creative idea requires deviating from conventional modes of thought, quirkiness involves deviation from conventional social behavior. If you ignore the rules in one domain, you may also ignore them in another. Once we form a stereotype of the erratic artist, we may see those who fit the stereotype more snugly as being better artists. (This applies to other stereotypes, too. In one study listeners liked rap songs better when they thought the musicians were black.)

For the New Paper, published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, Wijnand van Tilburg, of the University of Southampton, and Eric Igou, of the University of Limerick, conducted several experiments. First, they showed participants an image of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and told half that the painter was believed to have severed his own ear lobe. Viewers with this information liked the painting more. In another, participants looked at three pieces of art, and half were told that the (fictional) artist was personally eccentric. These subjects liked the works better and were willing to pay more than four times as much for them.

But maybe people simply like art more when they have more information about the artist? In another experiment, participants rated their enjoyment of the works from the second experiment, and also rated a photo of the fictional artist on eccentricity. Some saw a man with short hair and a white shirt. Others saw him with longer hair, facial stubble, and a vest. Those who saw the second man liked the work better, and this was specifically accounted for by his greater perceived eccentricity.

Being a weirdo doesn’t add credability in every situation, even in the art world. The researchers showed one group of participants a conventional artwork (Lady of Flowers) by Andrea del Verrocchio) and another an unconventional artwork (The Pack by Joseph Beuys), after first providing an artist bio. In each group, some were told in the bio that the artist spent much of his life carrying roadside stones on his head to his cottage. This addition boosted ratings of The Pack, but had little effect on Lady of Flowers. According to Van Tilburg, “there needs to be a ‘fit’ between artist eccentricity and the type of art being produced.” The kind of guy who carries stones on his head probably has an unconventional vision that will be expressed in his unconventional art. But as for Lady of Flowers, there’s not too much to be read into a bust of a lady holding flowers.

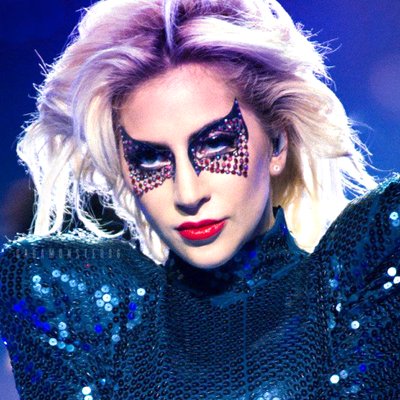

Finally, Van Tilburg and Igou delved into the phenomenon that is Lady Gaga. They showed some subjects a photo of her seated on a chair wearing a conservative dress, regular makeup, and a ponytail. Others saw her crouching in a tight black suit, with black boots and gloves and a shiny mask (the getup from the “Poker Face” video). Some also read that music critics consider her whole image to be a piece of strategic marketing. Then they all rated her skill as an artist and how much they like her music. Those who saw the “Poker Face” outfit liked her and her music better—unless they also read the critics’ calling her out. That is, if they didn’t believe her eccentricity was authentic, it earned her no points.

In a footnoted study, the researchers found that showing subjects eccentric images of Lady Gaga, Salvador Dali, and Björk did not influence ratings of art by other people, revealing that information about an artist’s eccentricity does not affect ratings of his or her work simply by triggering thoughts about creativity, or by causing participants to think more abstractly.

Even if you decide to scheme up a whole crazy artist persona, it’s likely that at least some people won’t see through the plot and will grant you greater regard. *I am crediting excerpts for this post to Jem Aswad of “Variety Magazine.

After being on the road with many well-known entertainers, I have seen about every ideocracy you can imagine. Of course, the stories are exaggerated for the press and I am sure they end up being good marketing tools.

On the late-night bus rides with the crew it is always entertaining to “one up” another crew member’s story of some artist’s weird habits. I could write a book on artists like Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, etc. etc. and all their “weird” eccentricities. There is no doubt it added to the mystic of the artist and may have drawn bigger crowds and sold more records, but the fact of the matter is they worked at their craft like anyone else, but no doubt, put in a few more hours of practice and hard work. As far as eccentricity, if you give anyone enough money and adulation of the crowds, if they are not well grounded in reality, you can bet their character will take a hit.